United Charities Building History

Nov 19, 2019

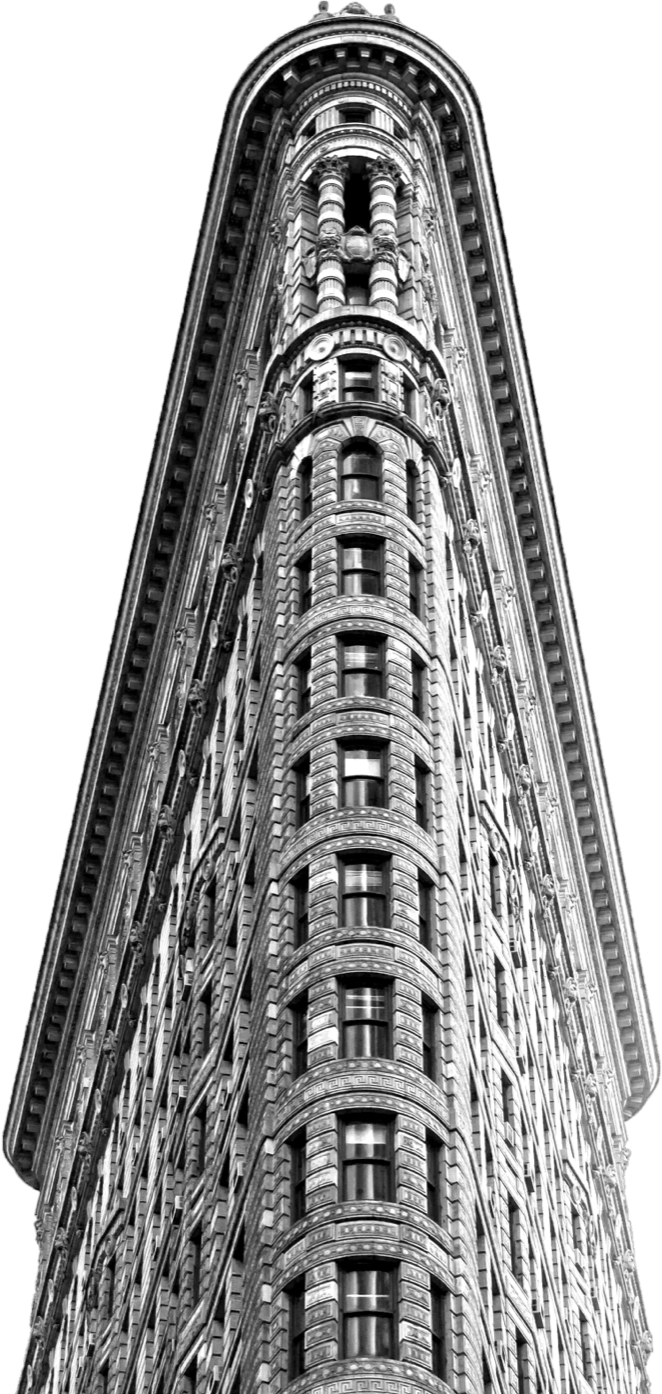

As we enter the 2019 holiday season of giving, the Flatiron Partnership offers a snapshot of the 1893 debut of the United Charities Building, a pioneer headquarters for a number of nonprofit organizations that provided social services to those in need. The Renaissance Revival-style building shared the address of 287 Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue South) and 105 East 22nd Street.

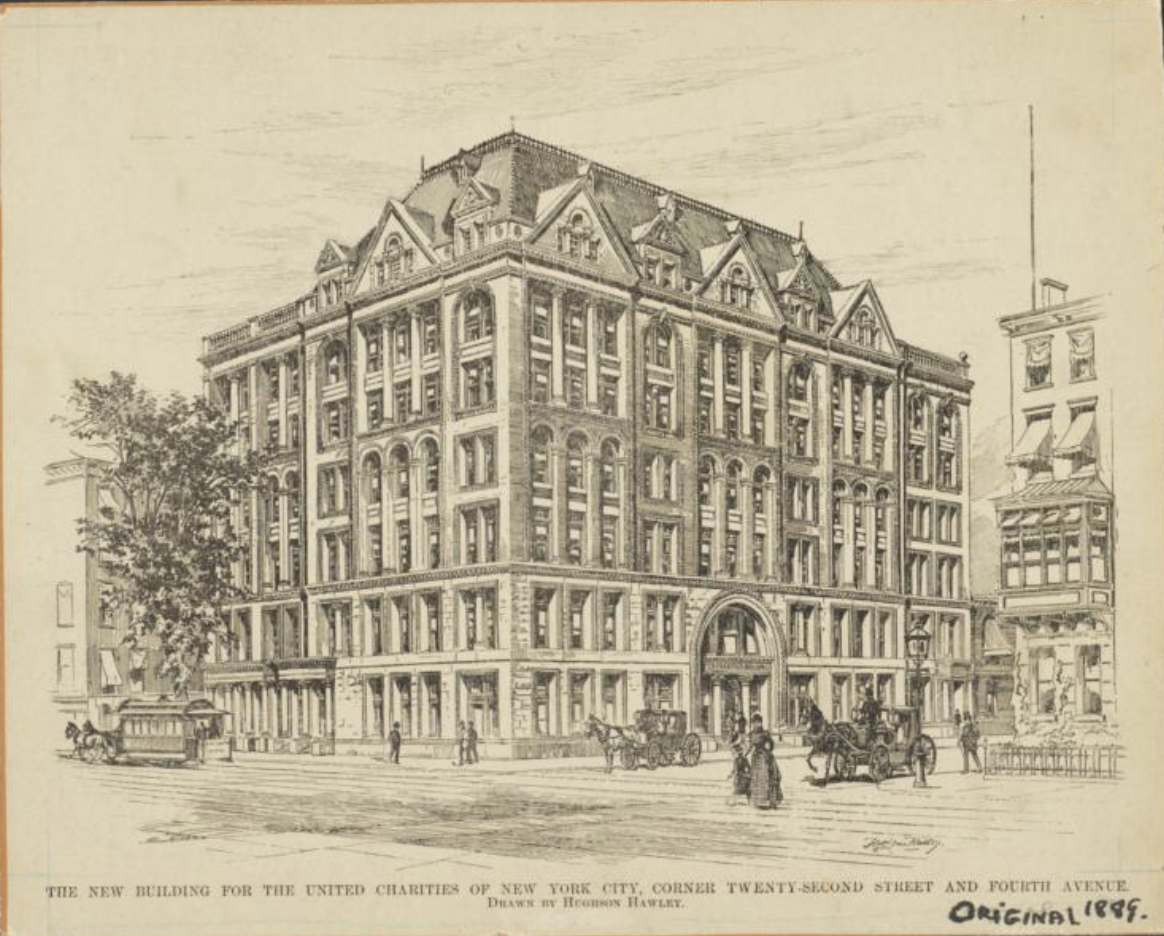

The location for UCB had been the former site of St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church, once described as “one of the most massive and strongly-constructed buildings in the city,” wrote The New York Times on September 24, 1891. Noted designer of homes in the Hamptons, Robert H. Robertson, and the team of Rowe & Baker, who had offices at 10 West 23rd Street near Madison Square Park, were the architects behind the blueprint for UCB. The land where UCB would be built had been purchased by New York philanthropist and banker John S. Kennedy for a reported $300K. The estimated total construction costs for the 121,059 square foot building was valued between $500K and $700K.

Kennedy nominated four organizations to inhabit UCB: the Children’s Aid Society, the Charity Organization Society, the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, and the New York City Mission and Tract Society. The nominated organizations were desingated to benefit from USB as, “The building is expected to be self-supporting, and any surplus revenue, after providing for maintenance and perhaps extension, will be devoted to the general purposes of the four societies named,” according to The New York Times on March 10, 1891. The day before UCB officially opened its doors for occupancy on March 6, 1893, a dedication service for the property was held at the location. Scheduled attendees at the event included political dignities such as former New York City Mayor Abram S. Hewitt and future Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr., as well as members of the City’s wealthy Gilded Age society such as financiers J. P. Morgan and Russell Sage.

(Drawing by Hughson Hawley From: King’s Handbook of New York City.

Planned, edited and published by Moses King, Boston, Mass. Copyright, 1892)

Other soon-to-be UCB occupants included The Hospital Book and Newspaper Society, the Society for the Prevention of Crime, and the New York Cooking School, which trained individuals “to cook cheap and nutritious food,” and “supply luncheon to all the employees in the building,” noted The New York Times on March 5, 1893.

During this era, a number of charitable organizations were headed by women. According to the book Landmarks of American Women’s History, the National Consumers’ League was “one of the most influential women’s reform organizations” and the group decided to locate their offices at UCB in 1899.

In addition to the offices that were being used by the charities, UCB featured five elevators, an assembly hall, artists’ studios, and ground-level space for two stores as well as a Penny Provident Fund branch, which promoted itself as a financial institution that would “better safeguard” the accounts of its low-income clients. There were also “free baths to be managed by the Children’s Aid Society,” according to The Times.

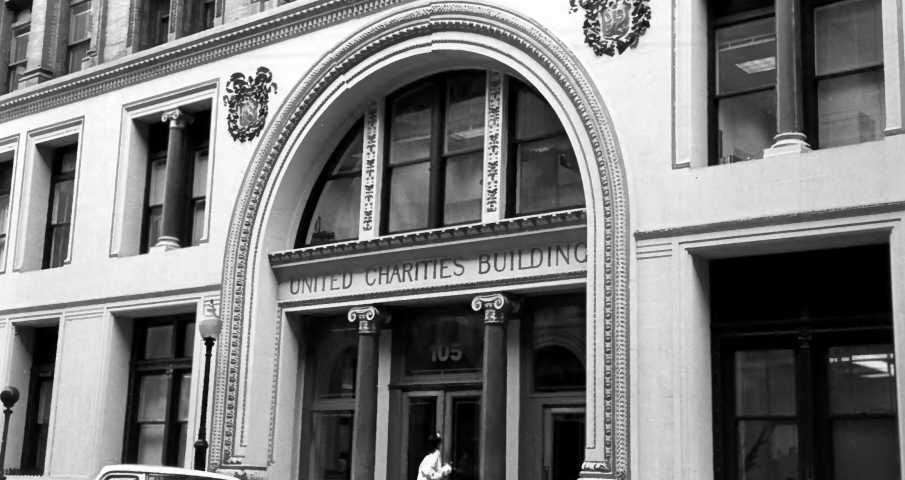

One of the most appealing architectural aspects of UCB was its entranceway. In a 1986 report issued by the National Register of Historic Landmarks about UCB’s pending status as a landmark, the entry doors were described as being “flanked by granite Ionic columns. The arch is enhanced by guilloché, egg and dart, and bead and reel patterns. On either side of the arch are decorative cartouches. Surmounting the entrance is the legend United Charities Building in bronze letters, and a tripartite semi-circular window with floral pilasters.” Five years later, on July 17, 1991, and nearly a century after its opening, UCB was designated a National Historic Landmark.

(Picture by Beyond My Ke vis Wikipedia)

But in 2014, and for the very first time in the building’s real estate history, UCB went on the market to be sold. The property was purchased by a developer for a reported $128 million, with the intent to build condominiums. “This deal is part of a larger trend, where nonprofits city-wide are taking advantage of a hot condo-development market and selling off their headquarters, downsizing to smaller ones or moving to less pricey areas,” reported the website Curbed New York on September 14, 2014.

Following a gut-renovation of the property, however, Spaces, a global office and room provider, became UCB’s newest occupant leasing more than 100K square feet in the mixed-used property, noted published reports. And acclaimed British steakhouse Hawskmoor indicated its first U.S. restaurant would open at the building’s ground-level location.

The legacy of charity launched by financier John S. Kennedy, however, still maintains an active role within the Flatiron District today. The UCB founder’s idea of a place “to which all applicants for aid might apply with assurance that their needs would be promptly carefully considered” continues more than a century later, with almost 30 nonprofit organizations that offer various services throughout the community.

Header Photo Credit: National Portrait Gallery